Bone Class Internals

The purpose of this page is to explain how a bone is implemented in Babylon.js, and in particular which matrices are used internally to calculate the final transformation matrix of the bone. If you want to manipulate bones manually, or simply understand how they work, this page is for you, as it's not easy at first to understand how everything works together.

Note that we won't be going back over the basics of bones, so if you don't know what a bone is, or how it works, first read the Bones and skeletons page.

Bone class generalities

The Bone class extends Node and not TransformNode, which may seem surprising at first glance since position/rotation/scale only exists in TransformNode and not in Node, but this is for historical reasons.

This means that Bone implements its own position/rotation/scale properties, and that a bone will not appear in the scene node hierarchy displayed by the inspector, since only transform nodes (and derived classes) are displayed in the hierarchy.

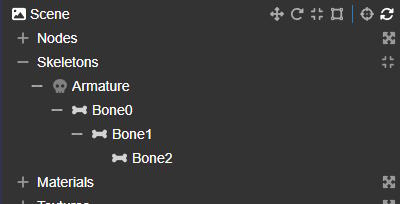

Bones only appear as child nodes of a skeleton, under the Skeletons entry in the Inspector:

Bones have a length property, which is not used directly by the class. It's mainly used by the BoneIKController class, which needs it for leaf bones.

The last bone in a chain is not connected to any other bone, so it's not possible to calculate its length (which is in fact the distance between the bone's position and the position of the child bone).

An ad-hoc length is therefore required for the last bone in a chain, which is why the length property is used.

Linked TransformNode

Each bone can have a linked TransformNode (which you can retrieve with a call to Bone.getTransformNode()), in which case it's this node that will undergo the transformations (through animations, for example), and the transformations of this node will be copied into the bone (this copy is made in Skeleton.prepare).

This mode has been added to handle skeletons loaded from gltf/glb files, where the skeleton bones are in fact regular nodes in the scene node hierarchy.

It's important to understand that when a bone is linked to a transform node, modifying the translation/rotation/scaling of the bone will have no effect; instead, you need to update the linked transform node!

More information on this subject can be found in glTF 2.0 Skinning.

Bone matrices

This is where things get complicated (or interesting)!

The Bone class uses 7 matrices internally to do its work. This can be confusing at first, so let's try to categorize and describe them:

| Internal property | Public access | Description |

|---|---|---|

Internal property _localMatrix | Public access Bone.getLocalMatrix() | Description This matrix is the one that stores the current local space position/rotation/scale of the bone. You can think of it as the main matrix, as it's the one that will actually move/rotate/scale the bone. However, as with the transform nodes, you won't be modifying the matrix directly, but updating the position/rotation/scale properties instead (either of the bone, or of the linked transform node if the bone is using this mode). |

Internal property _absoluteMatrix | Public access Bone.getAbsoluteMatrix() | Description This matrix stores the bone's world transformation matrix. This is the transformation you get when you multiply the bone's local matrix with all the local matrices in its parent hierarchy. |

Internal property _finalMatrix | Public access Bone.getFinalMatrix() | Description This matrix stores the final transformation of the bone (after the bind matrix has been removed, that is after _absoluteInverseBindMatrix has been multiplied with _absoluteMatrix - see below), in world space. This is the matrix that will be used in the vertex shader to transform the vertices. |

Internal property _bindMatrix | Public access Bone.getBindMatrix()Bone.setBindMatrix() | Description This matrix stores the bone transformation (in local space) that corresponds to the bind pose, i.e. the bone position/rotation/scale that is the "natural" bone transformation. This transformation acts as an "identity transformation", as it is removed from the bone transformation (the local matrix) before being used to transform the vertices. So, if the local matrix of a bone is the same as the bind matrix, removing the bind matrix will result in the identity matrix, meaning that the vertices attached to that bone will not be modified by that bone. This is normally the bone transformation defined at the time of creation. |

Internal property _absoluteBindMatrix | Public access Bone.getAbsoluteBindMatrix() | Description This matrix stores the bone transformation (in world space) that corresponds to the bind pose. Normally, you shouldn't need to access this matrix; it's mainly used to calculate the absolute inverse bind matrix (see below). |

Internal property _absoluteInverseBindMatrix | Public access Bone.getAbsoluteInverseBindMatrix() | Description This matrix stores the inverse matrix of _bindMatrix, in world space. It is the matrix used to remove the bind transformation from _absoluteMatrix. |

Internal property _restMatrix | Public access Bone.getRestMatrix()Bone.setRestMatrix() | Description This matrix is a user-defined matrix and is not used by the internal workings of the Bone class. You can use this matrix to define a bone transformation as the "rest" matrix and easily return to this transformation at any time by calling Bone.returnToRest() (you can also do this for an entire skeleton by calling Skeleton.returnToRest()). By default, the rest matrix is initialized with the bind matrix, which means that calling Bone.returnToRest() will place the bone in the bind pose. |

This table shows that there are really only two matrices that can be described as "dynamic", the other five being described as "static":

- the local and final matrices are (or can be) updated frequently (every frame).

- the absolute matrix is not permanently updated! It is only updated when you call methods that need to access this matrix (such as

Bone.getPositionorBone.getDirectionin world space). If you need to access this matrix yourself, you should first callBone.computeAbsoluteMatrices()to make sure it's up to date. - all other matrices are only updated if you modify the bind matrix (absolute bind and absolute inverse bind matrices) or if you modify the rest matrix. In most cases, these matrices are never updated after a bone has been created.

Notes:

- the final matrix is relative to the root of the skeleton: in a final step, this matrix is multiplied by the world matrix of the mesh to which the skeleton is attached (this is done in the vertex shader).

- the bind matrix is only used to calculate the absolute bind and absolute inverse bind matrices. Once the absolute bind and absolute inverse bind matrices have been calculated, the bind matrix is no longer used (nor is the absolute bind matrix, as we only need the absolute inverse bind matrix).

Ultimately, as a user, you should only be concerned with the local matrix, but indirectly, through the position/rotation/scale properties of the Bone class (or the linked transformation node if the bone uses this mode).

Details of class operation

If you look at the source code, you'll see an additional matrix (not exposed to the end user, as it's labelled "@internal") with a getter and a setter: _matrix. This is not a new matrix, but an alias of the _localMatrix property!

When you call Bone.computeAbsoluteMatrices(), the implementation assumes that the absolute matrix of the parent is already up to date! If you're not sure, you should call Skeleton.computeAbsoluteMatrices() to update the absolute matrix of all bones in the skeleton. Note that Bone.computeAbsoluteMatrices() also updates the absolute matrix of all the children of the bone.

Only the bind and rest matrices have a setter, Bone.setBindMatrix() and Bone.setRestMatrix() respectively. When Bone.setBindMatrix() is called, the absolute bind and absolute inverse bind matrices are also recalculated (and for the children of this bone too).

The implementation of the absolute bind and absolute inverse bind matrix calculation (in Bone._updateAbsoluteBindMatrices())) assumes that all parent bones in the hierarchy have already been processed and are up to date! So, if you're updating the bind matrix for several bones yourself, you need to make sure you're updating them in the right order. Another solution is to update the bind matrices in any order you wish, EXCEPT for the root bone, for which you must call Bone.setBindMatrix() last, as setting the bind matrix for a bone will calculate the absolute and absolute inverse bind matrices for that bone as well as for its children.

The class supports the rotation and rotationQuaternion properties to update the orientation of the bone, but internally the orientation is stored as a quaternion. This means that if you update rotation, a conversion to a quaternion must take place. So, whenever possible, you should use rotationQuaternion to gain a tiny bit of performance.

To speed up the calculation of final matrices for all bones in a skeleton (in Skeleton._computeTransformMatrices), we assume that bones are sorted in such a way (in Skeleton.bones) that parents come before children. This means that when we calculate the final matrix of a bone, we can assume that the final matrices of all its parent bones have already been calculated. So, if you're creating a skeleton manually, you need to make sure that the bones are in the right order in the skeleton's bone array: Skeleton.sortBones() can do this for you.

Understanding the bind matrix

If you're not familiar with how bones and skeletal animations work, the bind matrix can be a little confusing, and you may not immediately understand its usefulness. So let's try to explain what it is and how it works.

Let's take an example to support this explanation:

| Mesh | Skeleton view | Skeleton hierarchy |

|---|---|---|

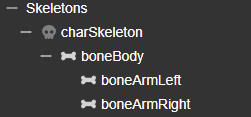

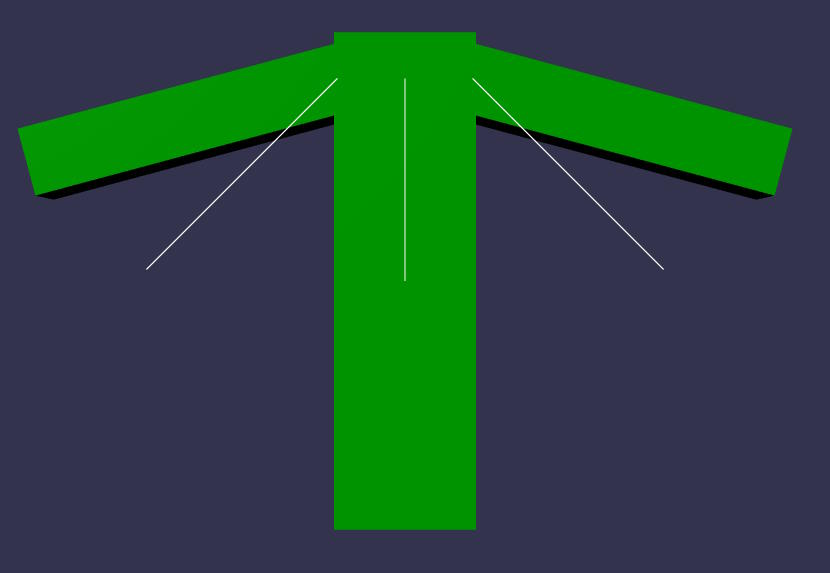

Mesh  | Skeleton view  | Skeleton hierarchy  |

Here's the PG we'll be using throughout this section, which can also be used as an example of how to create a skeleton and bones programmatically:

Character exampleAs you can see above, there are three bones, one for the body, one for the left arm and one for the right arm. We first created three separate meshes (body, left arm, right arm), assigned bone indices and weights to each, then merged them into a single mesh, to simplify the example. Bone indices and weights are very simple:

- all body points: weight=1, bone index=0

- all points on the left arm: weight=1, bone index=1

- all points on the right arm: weight=1, bone index=2

In the skeleton view, each line represents a bone. However, boneArmLeft and boneArmRight are leaf bones, so they wouldn't normally be drawn because this line connects the position of the current bone to the position of the next bone, but in this case there is no next bone. To obtain a representation of the bone, we used the length property of the Bone class. In this case, the line is drawn from the bone position to the bone position plus the bone length.

The skeleton view is probably what you'd expect in terms of bone position and orientation: the bones of the left and right arms follow the orientation of the corresponding meshes and start at the shoulder. This is because we provided a specific translation and orientation at the time of bone creation: this is the bind pose (or bind matrix, as internally the position/orientation will be transformed into a matrix). This is also the initial value for the local bone matrix, as we want the bones to visually be in this position/orientation.

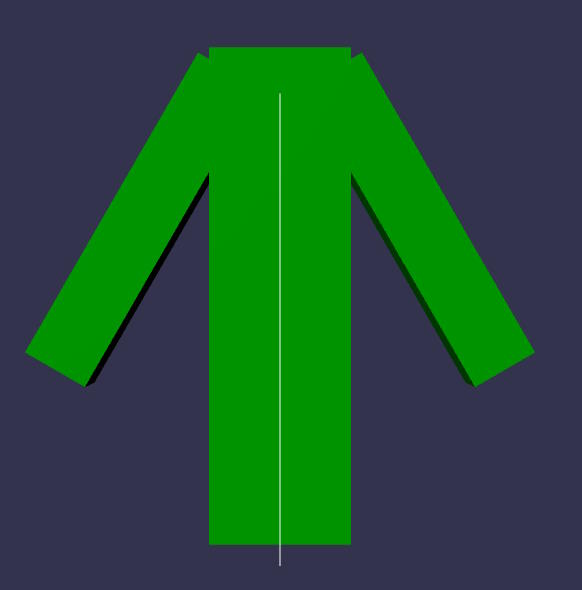

However, this initial transformation is totally arbitrary. We could also pass a translation (0,0,0) and no rotation:

| No translation, no rotation | Translation at shoulder, no rotation |

|---|---|

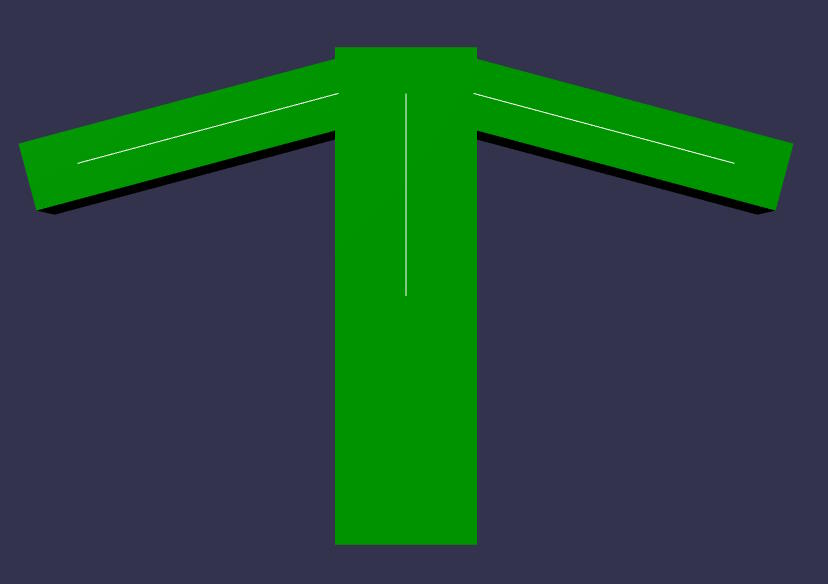

No translation, no rotation  | Translation at shoulder, no rotation  |

You can't really see what's happening in the first case, because all the bone positions are at the origin, so I've created a second example where the translation is not zero, but the rotation is still the identity rotation matrix.

As you can see, this is perfectly valid and the character is always displayed correctly. This is because the bind matrix is removed from the bone local matrix before being used to update the mesh vertices. Removing the bind matrix means that:

- the bind matrix position is subtracted from the current bone position

- the x/y/z rotations of the bind matrix are subtracted from the x/y/z rotations of the current bone orientation

- the x/y/z scale of the current bone matrix is divided by the x/y/z scale of the bind matrix.

We must remove the bind matrix because, when we're not animating the bones (when they're in the "starting" pose, i.e. when the local matrix is equal to the bind matrix), we want the vertices not to be modified by the bone transformation, i.e. to be in the same position as when the mesh was created. To achieve this, the final matrix must be equal to the identity matrix, which is the case when the bind matrix is removed from the bone transformation. Mathematically, B-1 * L is the operation that removes the bind matrix (B) from the local bone matrix (L). When L = B (we're in the "starting" pose), B-1 * B = I (identity matrix), so the vertices are not modified by the final bone matrix.

As explained above, using the identity matrix (or any other matrix, for that matter) for the bind matrix is perfectly valid, so we could get rid of the bind matrix altogether: the bind matrix would be the identity matrix for all bones and we wouldn't need to supply it.

However, this complicates things considerably when you start animating the character. It's much more intuitive to animate a character when the bones are in a natural position/orientation in relation to the underlying meshes than to use a default position/orientation.

See:

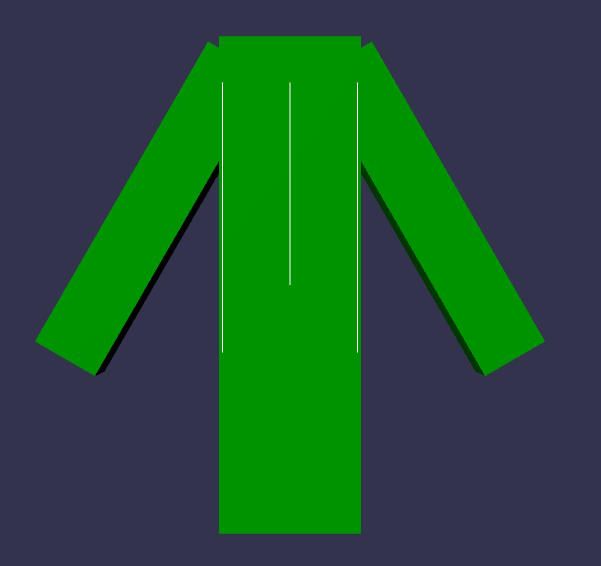

| Translation at shoulder, no rotation | Natural translation/rotation |

|---|---|

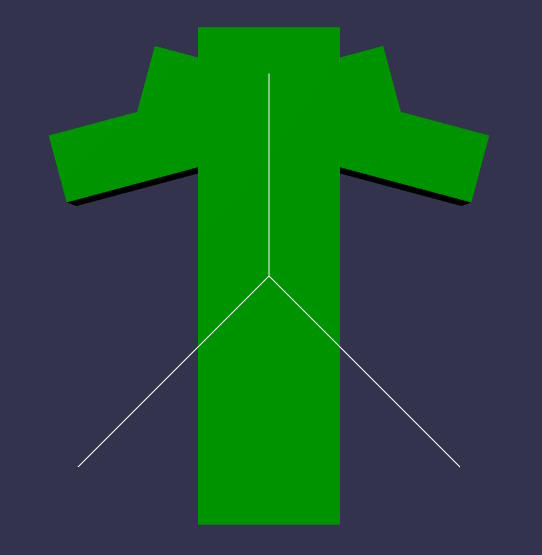

Translation at shoulder, no rotation  | Natural translation/rotation  |

The final rendering is the same in both cases, so both methods are valid, but the second is much easier to animate when the final rendering corresponds to the position/orientation of the bones.

Note: the local matrices of the arm bones are not the same in both cases! For the left arm:

- in the first image, rotation around the Z axis is 45°. As the bind matrix is the identity matrix, the rotation around Z is 0°, so the rotation around Z in the final matrix is 45-0=45°.

- In the second image, the rotation around Z is 75°! This is because the bind matrix has a rotation of 30° around Z, so that the left arm bone matches the visual appearance of the mesh. So, to obtain a final rotation of 45° around Z, the rotation around Z in the local matrix must be 75°. So, after removing the bind matrix, the rotation around Z in the final matrix is 75-30=45°.

You can see that the end result is the same in both cases (45° rotation around Z), which is why the final rendering is the same, but we achieve it in two different ways.

Using a translation (0,0,0) for the bind matrix makes things even more difficult:

| 45° rotation around Z | 45° rotation around Z and (1.2, 0.08, 0) translation |

|---|---|

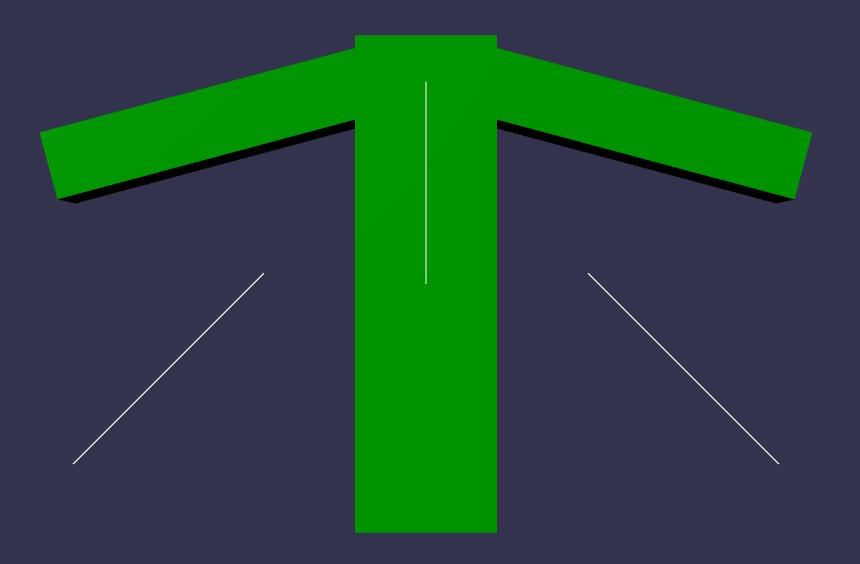

45° rotation around Z  | 45° rotation around Z and (1.2, 0.08, 0) translation  |

To obtain the same final rendering (for the left arm), we have to apply not only a 45° rotation around Z to the local bone matrix, but also a translation of (1.2, 0.08, 0)! This is considerably more difficult than above, and you can see that the bone positions/orientations are completely out of sync with the mesh.

Animation data generated by DCC tools

DCC (Digital Content Creation) tools (such as Blender) generate animation data for bones in the form of matrices. These matrices are the local matrices of the bones, and as such also contain the transformation brought about by the bind matrix.

For example, in the first playground where we've created the bones with a bind matrix that corresponds to the appearance of the mesh, if we create an animation with a single frame and this frame renders the mesh in its "rest" position, we'll export a rotation of 30° around Z for the left bone, and -30° for the right bone: we'll simply export the current local matrix of each bone. This is what Blender (or any other DCC tool) would do: for each frame of the animation, it would export the local matrix of each bone.

This is compatible with our way of dealing with bones: when rendering, we remove the bind matrix from the local matrix (in fact, we do this calculation in world space, so we remove the absolute bind matrix from the absolute matrix), so in the example above, we'll render the mesh unmodified by the animation data.

Note that we need to know the bind (or inverse bind) matrix for each bone, so this information is also exported by the DCC tool, but in a section other than the animation section (in glTF, it's exported in the "skins" section), as the bind matrix doesn't change during an animation, it's a bone invariant.